As the Asheville community looks at how to best remedy its lack of recognition of the African American community and their contributions and sacrifices that made Asheville what it is today, it is more important than ever to know MORE history. What did slavery look like in Asheville and Buncombe County? These are a few notes taken from Asheville newspaper reportage from 1850-1863.

But first, HOW MANY SLAVES WERE THERE IN BUNCOMBE COUNTY?

In 1850 Buncombe County had 1,717 slaves and 107 Free Blacks. The total population was 13,425.

In 1860 Buncombe County had and 1,907 slaves and 283 slave owners. There were 111 Free blacks. The total population was 12,654.

Lawyer, legislator and planter, Nicholas W. Woodfin (1810-1876) owned the most slaves in Buncombe County, which numbered 122. He acquired extensive acreage in the French Broad Valley and his home was approximately at the site of the HomeTrust Bank at the intersection of Broadway and Woodfin Street.

[Slave figures from the 1850 and 1860 United States Census Bureau of Slave Schedules; see also, Slavery, Civil War and Freedom” by Terrell T. Garren.]““““

WHERE WERE SLAVES SOLD? We’ve recently had several people ask us if slaves were sold at the Court House.

From newspaper research it appears that the sale of slaves generally took place on the property of the seller or recently deceased, including many estate sales.

Harriet Alexander (1816-1897), the daughter of James M. and Nancy Alexander married Elisha Ray and they had four children. They resided at the mouth of Beaverdam Creek. After Elisha died in 1844 she married Richard Sondley in 1855 and they had one child, F.A. Sondley (1857-1931), whose antique book and ephemera collection of some 35,000 volumes forms the nucleus of the North Carolina Room’s collection.

Robert Ingram was born in Ireland in 1768 and died in Buncombe in 1857. He is buried in the Old Ingram Cemetery in Black Mountain.

SLAVES SOLD AT THE COURTHOUSE

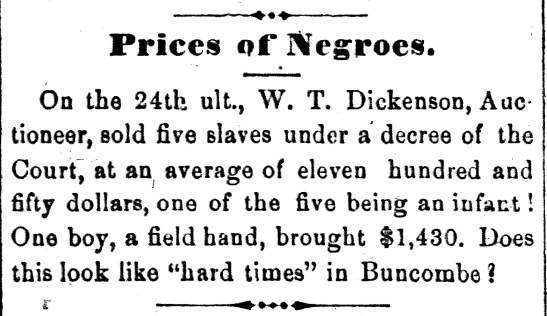

A few sales of slaves did occur at the Buncombe County Court House, generally as an estate sale. Only two of these types of sales have been documented at this point from 1850-1863. Note the announcement below was a “Decree of Equity” which usually involved a bankruptcy or divorce. The Courthouse at this time was built of brick in 1848-50 by Ephriam Clayton and stood about the site of the Vance Monument. It was said to have been a handsome building in the Greek Revival style, as were the three brick Asheville churches Clayton was also the contractor for, Asheville Presbyterian, Trinity Episcopal and Asheville Baptist. Catherine Bishir writes in North Carolina Architects & Builders that, “Because Clayton’s trade was as a carpenter, when he contracted for brick buildings he used other men to accomplish the brickwork. Some may have been his slaves or hired artisans.” The Buncombe County Court House was destroyed by fire in January 1865. There are no known photographs of this building.

Elizabeth and Benjamin Hemphill (1824-1909) lived on Reems Creek and had several children including Salina, Lusene, and Samuel.

Elizabeth and Benjamin are listed in the 1850 census, but in the 1860 census, Elizabeth is listed as head of household. An interesting article in the Asheville Citizen-Times of May 18, 1901 tells about Benjamin Hemphill returning to Buncombe after having left here in 1852, almost a half century earlier. He left a wife and three small children and took with him “four negro slaves.” He spent most of his time away in British Columbia. Elizabeth is buried in the Brank Cemetery on Reems Creek Road. Without Benjamin.

The second announcement found of slaves sold at the Court House were from the estate of John P. Smith.

John Patton Smith (1823-1857) was the son of James McConnell Smith (1787-1856.) In the 1850 census James owned 44 slaves and when James died, his son John P. Smith inherited property and 10 slaves which included “Joe the wagoner.”

Several ads by James P. Smith occur for sale of his father’s property, but John died less than two years after his father on December 24, 1857 at the age of 34. This would explain the sale of slaves owned by him. [Information from “History of the Smith-McDowell House” by Dr. Richard Iobst, Biography Newspaper Files, North Carolina Room.]

Quite a few articles report on the prices recently gotten for slaves. There was an 1863-64 recession, but as the author of this article notes, it didn’t seem to be affecting the price of slaves.

Many slave owners in Buncombe County hired out their slaves.

Thomas T. Patton was a farmer and at one time kept the Mountain House in Black Mountain as a public resort.

The use of slave labor was an important part of Asheville’s growing tourism industry. Slave owners in Buncombe County often used slaves to help with their businesses, including hotels. James McConnell Smith, mentioned above, owned one of the first hotels in Asheville, the Buck Hotel, often called Smith’s Hotel. This ad points to a new owner of the hotel after Smith’s death. Note the use of “servants” in the hotel and that “children and servants” of those who stayed there were charged “two thirds price.”

W.T. Dickenson set himself in business as an auctioneer in Asheville, selling white resident’s property–which included, at that time, slaves.

Captain W.T. Dickenson was a prominent farmer of Ivy, a member of the Buncombe Riflemen, and a Mason. He died in 1889.

John Inscoe, in Mountain Masters: Slavery and the Sectional Crisis in Western North Carolina, page 83,–an excellent read for more information on slavery in Western North Carolina–says that “young slaves were often bought as long-term investments.” From the ads viewed, however, it seems that children were often bought for labor.

It seems surprising that no ads were found using the word “slaves” rather than “Negroes,” making it seem that the two were synonymous. I have not been able to find any information on why the word “slaves” was not used in Asheville.

The stamped figure of what appears to be a black woman walking with a cane and holding a bag–and placed on a stand–was used for almost all advertisements of sales of slaves. Sometimes, it was accompanied by a black male figure, also stooped over and also with a cane. This seems incongruous with the idea of Negroes being offered for sale who would be of strong working ability. It appears to have been the stamp that Asheville newspapers used. A few searches in other nearby towns showed ads without any illustrations.

Post by Zoe Rhine, North Carolina Room librarian

It should not be surprising, that in that era, infamous for weasel-word euphemism, “slave” was not a common word used in print. After all, this is America, the land of the free and home of the brave! we got no slavery here! Except for “Negroes”, of course: that’s (somehow) “different” (it’s called ‘cognitive dissonance’). And it has required a great civil war, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, “Strange Fruit”, the ACLU, the NAACP, ML King, jr, Rosa Parks, Selma, Woolworth’s, and it’s still not fixed. But it’s also not still “the same”, either.

The images were printing types (basically clip art made from engravings) and are similar to the ones used for runaway ads and posters for fugitive slaves—thus the walking stick and/or bindle.

Thanks for this research which brings slavery to the ground we walk on daily. The posture of the illustration of the woman to my eye is not that of someone old and needing a cane, but strong – the staff she holds might be a tool.

It’s so shocking to see the truth of slavery in old newspaper reports. I’m from Australia and while I don’t think we had slavery as such, we have a stolen generation (Aboriginal children taken from their families and placed in institutions) and often when the children got older they were sent out to work placements and the government stole their wages. As terrible as this was, it’s the same as actually owning people. I can’t imagine the horror hidden within these notices – the families that might have been broken up, the fear and terror. I also noticed that between 1850 and 1860 the number of slaves had gone up by almost 200 but the number of free blacks living in the area were only 4 more. Thanks for helping to educate me about slavery in the era. Oh, that was the other quite shocking thing – that slavery was around in such a relatively ‘modern’ era. How many history lessons, how many books have I read set in such an era where slavery was completely ignored. I can’t imagine, though probably a lot.

Oops – missed the “not” in “not the same” argh!

[…] NC because it opened up the region to the eastern seaboard. As we saw in a previous post “Some Notes on Slavery in Asheville and Buncombe County,” many slave owners in Buncombe County “hired out” their slaves. Initial work […]

[…] some details of Woodfin’s tenure as the county’s largest slaveholder. You can read them HERE, and […]

[…] Some Notes on Slavery in Asheville and Buncombe County, Pack Memorial Library, 2017 […]

[…] grog to weary travelers, carrying their bags, and cleaning their rooms for no pay. In 1860, some 1,900 enslaved people lived and worked in Buncombe County — not a large number, but enough to debunk the myth that there was no slavery in Appalachia (and, […]